Evaluation of the Reorganization Value of Delisted Companies

Evaluation of the Reorganization Value of Delisted Companies

This article combines the theoretical analysis and practical experience of the bankruptcy reorganization case of five companies, including Harbin Gongda High-tech Industrial Development Co., Ltd..undertaken by Lawyer Nafisa Nihmat's team in 2023, one of the “national bankruptcy classic cases” in 2023, and approximately 50 delisted companies in recent years. It discusses the unique reorganization value, reorganization paths, and common controversial and difficult issues in the practice of delisted companies under Chinese law.

I. Introduction

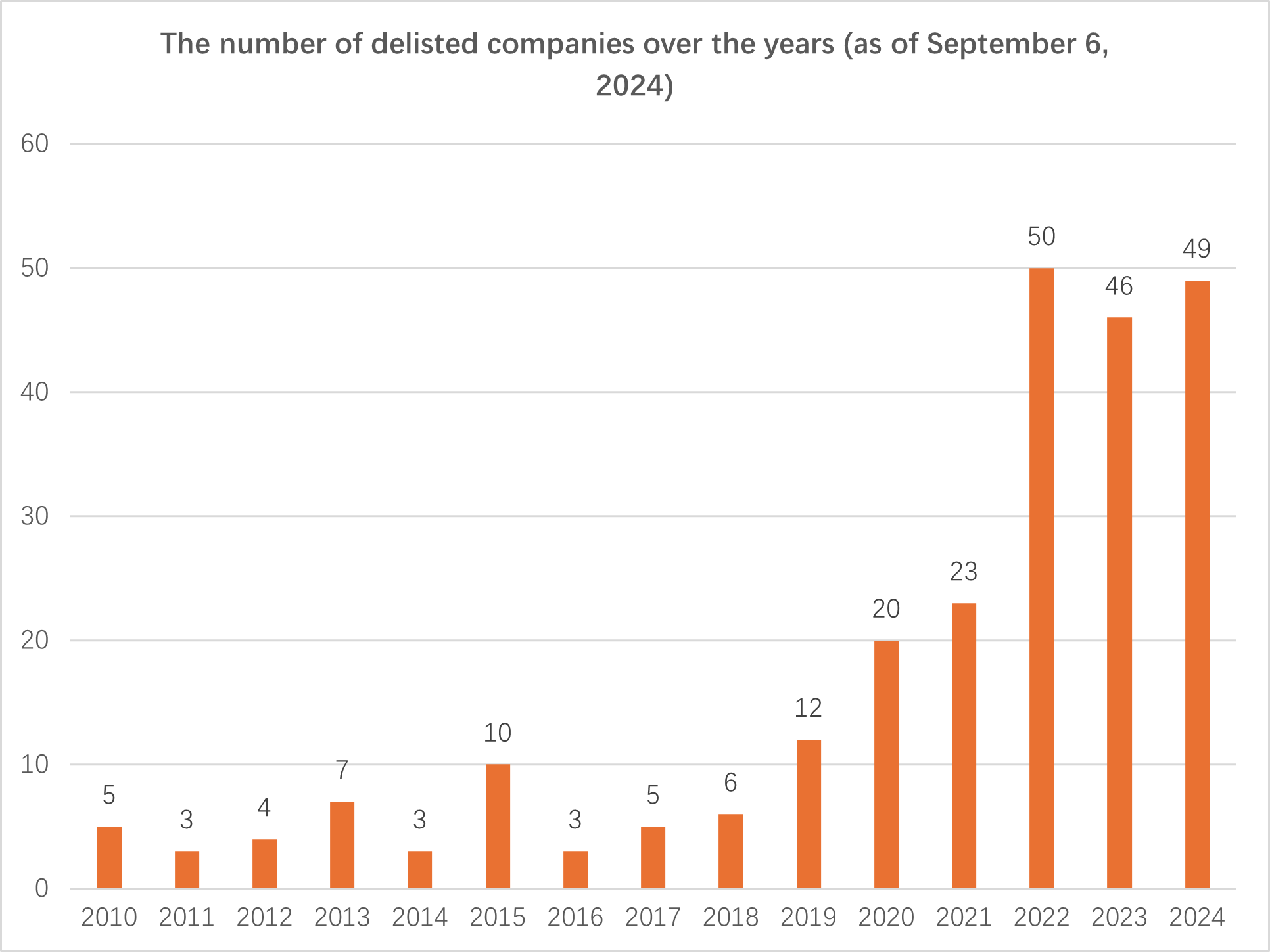

In April 2024, a series of regulatory measures were introduced to bolster oversight and mitigate risks in China's capital market, led by the “Several Opinions on Strengthening Supervision, Preventing Risks, and Promoting the High-quality Development of the Capital Market” issued by the State Council, and the “Opinions on Strictly Implementing the Delisting System” from the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC). Additionally, China’s stock exchanges issued operation rules such as the “Shanghai Stock Exchange Stock Listing Rules (Draft for Comment)” and the “Shenzhen Stock Exchange Stock Listing Rules (Draft for Comment)” (hereinafter collectively referred to as the “Nine National Opinions and Related Supporting Documents”). The Nine National Opinions and Related Supporting Documents aims to strengthen market supervision and advocate the normalization of delisting. Prior to 2019, the number of delisted companies was relatively low, with the annual count typically residing within a single-digit range. Since 2019, however, the delisting process has gradually gained momentum. In 2020, 20 companies were delisted; in 2021, the number increased to 23; in 2022, it further rose to 50; in 2023, 46 companies were delisted; as of September 6, 2024, 49 companies have been delisted. As an integral part of the overall delisting system, the avenues available to delisted companies after their removal from the stock exchange have attracted the attention of academia and the market, with a focus on the bankruptcy reorganization of delisted companies.

II. Evaluation of the Reorganization Value of Delisted Companies

(I) Comparison of the Differences in Reorganization between Delisted Companies and Closed Companies

From the perspective of legal norms, the reorganization of closed companies mainly follows relevant laws and regulations such as the “Enterprise Bankruptcy Law” and the “Company Law”, while the reorganization process of delisted companies requires compliance with the provisions of the “Securities Law” on top of the abovementioned laws. Compared with closed companies, delisted companies also need to abide by information disclosure rules. In addition, delisted companies, by virtue of their solvent nature, possess a wider array of tools during the reorganization process. Besides improving and resuming business activities, the possibility of relisting, which, once achieved, can serve to meet the demands of operators and shareholders alike, presents an additional avenue for delisted companies.

The Asset-liability of Delisted Companies Usually Presents More Favorable Scenarios for Reorganization

Compared with closed companies, delisted companies often have more abundant debt repayment resources, higher proportions of mortgageable assets, more financial institution-related debts, higher intangible value, and larger historical operating scales. Numerous theoretical and empirical studies have proved that such distinctive financial traits of delisted companies make them more suitable candidates for reorganization process rather than settlement or liquidation procedures. Furthermore, delisted companies tend to have sufficient capital reserves, which can be utilized as a valuable source of debt repayment. Before the causes of their delisting occur, these companies often exhibit higher financial stability and profitability than their closed counterparts, coupled with more abundant accumulated capital reserves that can be transformed into share capital to satisfy creditors' claims in the reorganization process.

The Sound Operating and Management System of Delisted Companies Complements the Reorganization Process

The financial governance, personnel management, risk internal control, and other requirements of listed companies are more stringent than those of closed companies. Listed companies are mandated to make regular and major information disclosures throughout their operation and are subject to rigorous oversight of regulatory authorities and public scrutiny. Under the internal governance pressure and external supervision, the management systems of these companies tend to possess a degree of inertia, remaining relatively sound in the aftermath of delisting.

Not only does reorganization offer a chance for corporate governance improvement, but it also presents a unique opportunity for the administrator to secure regulatory approval for listed companies with a sound internal control system while enhancing operating efficiency. At the same time, the administrator can also make full use of the provisions on bankruptcy dismissal to adjust the existing management team, employee composition, and governance structure of the company to meet the industrial transformation and changes in employment demand of the reorganized company. Since the administrator has legally taken over the debtor, there is usually no dilemma of management control conflicts and governance structure paralysis. In this sense, the pre-existing sound management system of delisted companies, in concert with the low-risk adjustment and improvement of the management system in the reorganization, form a synergistic relationship that facilitates the reorganization process. For reorganization investors, they can also actively engage in the operation of delisted companies through early due diligence, signing confidentiality agreements, etc., to pave the way for future development.

Path Selection for Re-listing of Delisted Companies after Successful Reorganization

Relatively speaking, the standards for re-listing of delisted companies in terms of total share capital, equity structure, market value and financial indicators, sustainable operating capacity, governance structure, compliance conditions, etc. are no different from those of first-time issuers, but there are differences in approval subjects, approval time, disclosure requirements, etc.

First of all, compared with the process of an initial public offering, enterprises applying for re-listing may enjoy relative advantages in terms of time efficiency. For delisted companies, their applications for re-listing primarily entail submitting necessary materials to the stock exchange, after which, if the exchange approves an application upon review, the company may proceed with registering with the CSRC. This process simplifies the verification procedures of the CSRC, potentially reducing the overall time cost.

Secondly, the focus of information disclosure for re-listing companies is also different from that of first-time listing applicants. On the one hand, a delisted company has accumulated historical financial data and market performance data during the first listing, which may simplify the process of financial audit and information disclosure. On the other hand, companies seeking re-listing need to focus part of their disclosure on re-listing announcements and reports, including the reasons for their delisting in the first place, their operating conditions during the delisting period, the implementation of the reorganization plan, and specific measures to solve previous problems.

Finally, delisted companies are more likely to meet the requirements of the equity structure for re-listing after reorganization. Listed companies are mandated to maintain a minimum of 25% shareholding by public shareholders. Delisted companies, on the one hand, possess an established base of public visibility from the first listing; on the other hand, a large number of creditors may become shareholders of delisted companies through debt-to-equity swaps during the reorganization process, further amplifying total shareholding ratio of public shareholders, rendering the delisted companies more fitting for the foregoing public shareholding requirement for listed companies.

(II) Comparison of the Differences in Reorganization between Delisted Companies and Listed Companies

In 2023, a total of 25 listed companies in China applied for pre-reorganization, 15 of which were accepted by courts. Compared with the reorganization of listed companies, delisted companies have certain advantages in terms of reorganization timeframe, information disclosure, regulatory requirements, and reorganization value.

The Reorganization of Delisted Companies is Not Urgent and the Completion Rate is High

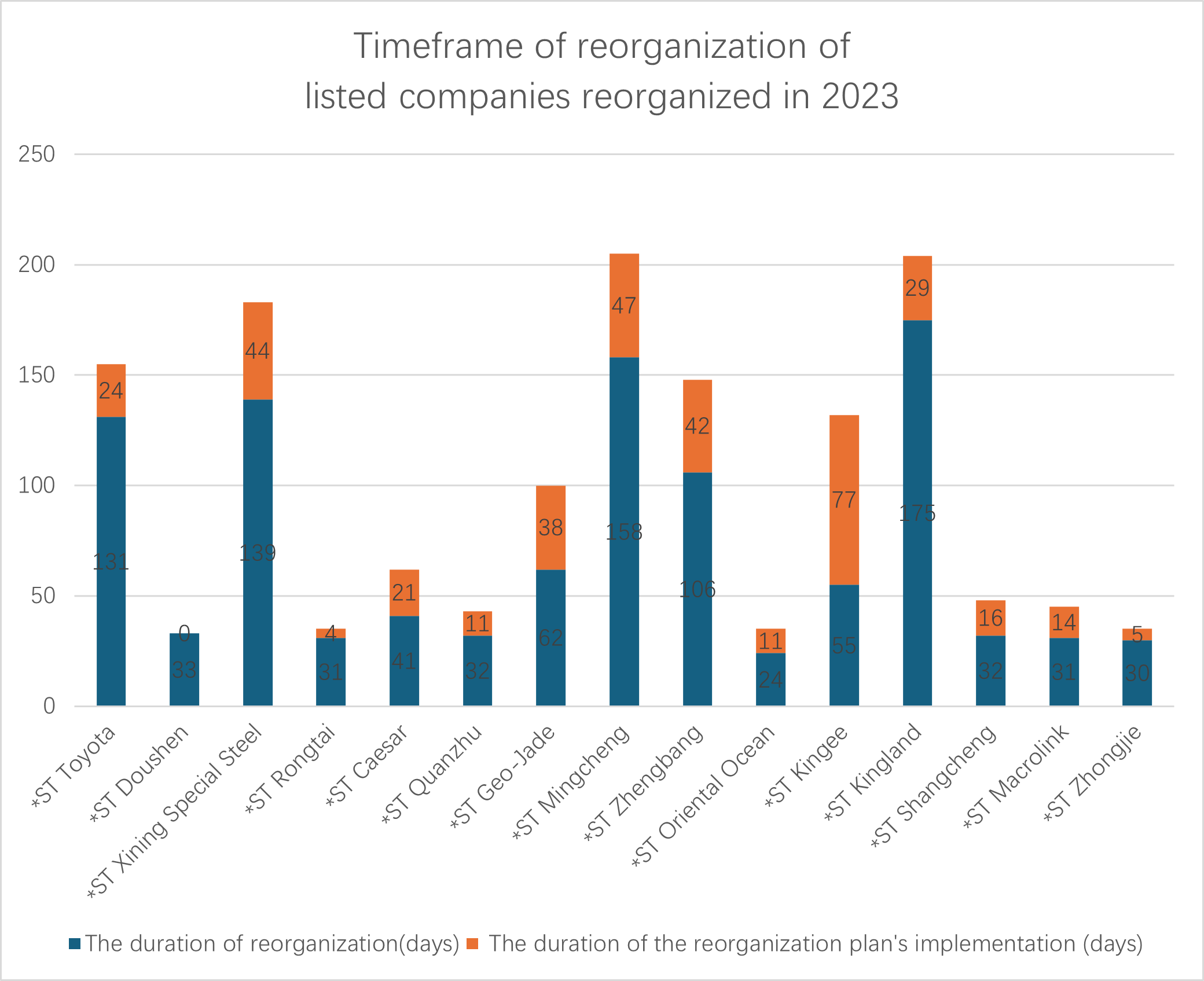

Due to the urgency of the risk of delisting faced by listed companies, the duration of reorganization (from the acceptance of reorganization to the approval of the reorganization plan) is usually compressed. According to the author’s research, among the 15 pre-reorganized listed companies in 2023, the average reorganization duration was a mere 72 days. Considering that the period for filing claims is generally at least 30 days, the time for claim examination, formulation of reorganization plans, determination the future operating plans, and the voting by each creditor group and contributor group, and even the court’s ruling, is extremely short. In fact, only one creditors’ meeting was held for 11 of these 15 companies.

In addition, listed companies usually set lower execution standards and shorter execution timeframes in the reorganization plans in order to get over with the reorganization plan in a short time. Among the 15 pre-reorganized listed companies in 2023, the average execution of the reorganization plan took 25.5 days. Considering that most of the repayment methods of listed companies include cash and capital reserve transfer in shares, and even trusts, the execution of the reorganization plan is almost a race against time.

By comparison, the reorganization of delisted companies tend to be much less urgent. Most delisted companies make full use of the provisions of the 6-month reorganization period plus a 3-month extension period, which helps an administrator effectively take over a company, sort out the asset-liability structure, and negotiate with the company’s management and investors on the reorganization plan and operation plan.

The Reorganization of Delisted Companies Involves Limited Information Disclosure and Regulatory Agencies, and the Approval Procedure is Simple

The acceptance of bankruptcy reorganization of listed companies is subject to the “dual-line approval” by the Supreme People’s Court and the CSRC as a pre-procedure. Listed companies undertaking reorganization must fulfill explicit information disclosure obligations during the process, and they are expected to present practical and feasible solutions to issues of fund occupation and illegal guarantees, if any.

The acceptance of bankruptcy of delisted companies does not apply to the above provisions, and is mainly carried out in accordance with the relevant provisions of the “Enterprise Bankruptcy Law”, where finding solutions to problems such as fund occupation and illegal guarantees is not a precondition for courts to accept the bankruptcy reorganization of delisted companies. In addition, unlike the suspension of trading of delisted companies, listed companies are still trading normally during the reorganization period, and the requirements for information disclosure and regulatory approval are more stringent.

The Reorganization of Delisted Companies Reflects the True Value of the Enterprise and Conforms to the Market-oriented Spirit of the Bankruptcy Law

Due to the differences in liquidity and publicity of the small- and medium-sized share transfer system, the remaining value of delisted companies has largely returned to levels that reflect market rationality. Although they may still have certain advantages compared with their closed counterparts, which may make them attractive to speculators, speculators have no way to know for sure that delisted companies can push forward reorganization as smoothly and quickly as listed companies do, and their re-listing efforts are also fraught with uncertainties.

Their capital risks and occupation costs are significantly higher than those of investing in the remaining resources of listed companies. By thus stripping these companies down to their intrinsic value, the bankruptcy process translates the market-oriented spirit of the Enterprise Bankruptcy Law into tangible action. Whether it be promoting bankruptcy liquidation, settlement, or reorganization, the priority remains upholding the principle of optimized allocation of market resources and minimizing waste of judicial and social resources such as secondary bankruptcy.

III. Issues Concerning the Confirmation and Settlement of Contingent Claims of Delisted Companies

The settlement of contingent claims is an urgent concern that must be addressed in the reorganization of delisted companies. Given that the issue of false statements is often a contributing factor to delisting, delisted companies are more prone to claims from shareholders for damages from false statements compared with listed companies. At the same time, the interplay between shareholder lawsuits and bankruptcy procedures also needs to be thoroughly discussed.

(I) Issues Concerning the Confirmation of Claims Arising from False Statements

First of all, claims arising from false statements of public companies that occur before the acceptance of bankruptcy should be categorized as bankruptcy claims. However, unlike general civil and commercial disputes, it is difficult for administrators (liquidation groups) to determine the amount of losses incurred by shareholder creditors based solely on the materials submitted by them (usually including routine materials such as identity information and transaction records of purchases and sales provided by the exchange). In practice, two approaches are primarily employed. The first is a people’s court issuing a guiding judgment to determine the core parameters such as the implementation date, disclosure date, benchmark date, and benchmark price of false statements, and more importantly, to determine the loss calculation ratio and method. Subsequent shareholder claims are examined and confirmed by administrators in accordance with the guiding judgment. The second approach is courts, the delisted company in question or its administrator (liquidation group) engaging a professional institution with appropriate qualifications to specifically establish a loss quantification model for the delisted company, and then input the securities trading records of the involved investors into the model for calculation. However, it should be noted that different institutions may adopt different models and calculation methods, and that the use of institutional loss quantification models may raise questions regarding their legal validity and rational application, which means in such cases courts still need to endow it with legality through the trial system.

(II) Interplay between Shareholder Civil Lawsuits and Bankruptcy Procedures

Whether it is the transition from lawsuits to bankruptcy procedures or vice versa, there are issues regarding the interplay between civil lawsuits fought over compensation for false statements of delisted companies and bankruptcy procedures.

When it comes to the transition from lawsuits to bankruptcy procedures, a key concern arises when shareholder lawsuits are pending while creditors file claims in the bankruptcy procedure. That is, even if the principal of loss determined by the lawsuit and the bankruptcy procedure is consistent, other costs related to the lawsuit, such as case acceptance fees and attorney’s fees in the lawsuit, may still occur. As such, administrators (liquidation groups) cannot confirm shareholder claims when the lawsuit is pending.

In terms of the bankruptcy procedures transitioned to lawsuits, which is common when the responsible entities for false statements implicate other entities besides the delisted company, and the reorganization procedure cannot fully cover shareholder compensation. In this case, creditors tend to file lawsuits against other responsible entities at the same time, requesting a judgment for joint and several liability.

(III) Reservation of Debt Repayment Resources for Contingent Claims

In addition to the generally suspended confirmation of claims, administrators (liquidation groups) face a practical dilemma concerning the uncertainty of shareholder compensation claims in reserving debt repayment resources for delisted companies during the reorganization process, specifically in relation to shareholder compensation claims. On the one hand, the number of shareholders is difficult to determine, and the amount of contingent claims is difficult to estimate, making it impossible to accurately calculate the reserves for debt repayment. On the other hand, most of the reorganizations of delisted companies currently adopt a small cash repayment method, and the repayment of shareholder claims is directly related to cash reserves. Even after the reorganization plan is approved, the same type of repayment method can be adopted for overdue claims.

IV. Conclusion

The reorganization of delisted companies has its distinctive features. This article delves into the similarities and differences between delisted companies and other types of companies in reorganization from multiple dimensions such as assets and liabilities of delisted companies, management, re-listing, reorganization timeframe, information disclosure and supervision, and reorganization value. It also analyzes two major practical difficulties in the reorganization of delisted companies, namely the adjustment of contributors’ rights and interests and the treatment of contingent claims. Since the delisting system has become the first line of defense for the survival of the fittest listed companies, it is imperative to adopt bankruptcy as a rigorous selection process . For enterprises without reorganization value, strict market-based liquidation should be carried out, while for enterprises with operation value, reorganization can be deployed, imbuing these enterprises with newfound vitality and resurgence potential.