Updated Judicial Interpretations for Antitrust Disputes

Updated Judicial Interpretations for Antitrust Disputes

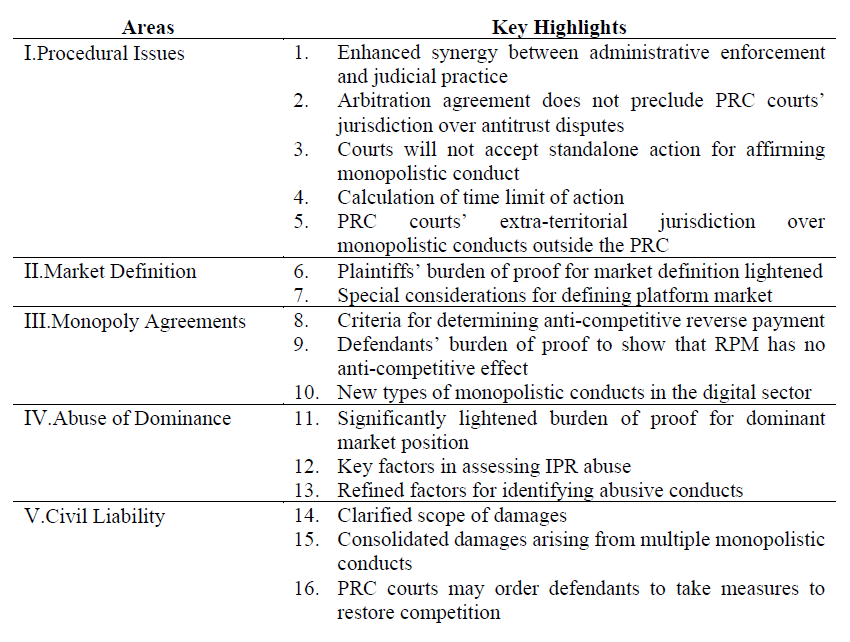

The New Antitrust JIs contains 51 articles (far exceeding the 16 articles in the Old Antitrust JIs), covering such areas as procedural requirements, market definition, monopoly agreements, abuse of dominance, and civil liability. While harmonizing with the Amended AML, the New Antitrust JIs also provides more detailed guidance for antitrust civil litigations, drawing on experience from Chinese courts’ judicial practice in antitrust cases over the past 16 years. This paper discusses the following key highlights of the New Antitrust JIs based on our experience and observations.

I. Procedural Issues

1. Enhance synergy between administrative enforcement and judicial practice

Firstly, in a litigation that follows a previous decision to impose an administrative penalty, the “basic facts” set out in the decision will be presumed valid, and the plaintiff will not bear the burden of proof for these facts unless there is sufficient evidence to invalidate the pertinent facts. However, compared with its most recent draft for comments, with regard to establishing monopolistic conducts, the New Antitrust JIs takes a more conservative stance, stating that judicial authorities will conduct an independent review and determination, instead of simply accepting the findings by an enforcement agency. In practice, we’ve observed courts’ adoption of findings in related administrative sanction decisions. In Miao v. SAIC[1], the SPC overturned the judgment of the court of first instance and held that since a penalty decision issued by the antitrust enforcement agency had found monopolistic conduct, the plaintiff in a follow-on civil antitrust dispute could rely on such finding, without the need for further proof. [Article 10]

Secondly, when necessary, a court may require the relevant enforcement agency to make a statement on the administrative enforcement findings and may also require the parties concerned to provide information on the relevant law enforcement, as well as previous arbitration or litigation. This provision may give more weight to pre-existing law enforcement in subsequent litigation. Therefore, litigants should carefully weigh the implications of materials submitted in the course of prior law enforcement, arbitration, or litigation cases. [Article 8]

Thirdly, if for an antitrust case pending legal proceedings, a concurrent investigation by an enforcement agency is ongoing, the court may decide to suspend the court proceedings, subject to the circumstances of the case. Firms with antitrust exposures are strongly advised to closely monitor the implementation of this provision in practice, as it may have a significant impact on the often adopted “two-pronged approach” where both litigation and administrative complaint are filed. [Article 13]

2. Arbitration agreement does not preclude PRC courts’ jurisdiction over antitrust disputes

The New Antitrust JIs provides that “where a party brings a monopolistic civil action to a people’s court, and the other party claims that the court shall not accept the action on the grounds that there is a contract and an arbitration agreement between the two parties, such claim shall not be supported by the people’s court”.

This provision reflects the Chinese courts’ clear stance against the exclusive jurisdiction of arbitration in antitrust matters arising from contractual disputes — the primary reason for the courts to take this position is that antitrust disputes by their nature have a public law element and implications for public interest, so the courts’ jurisdiction cannot be superseded solely on the grounds of private parties’ autonomy.

In certain recent judicial cases[2], compared with the position adopted in the New Antitrust JIs, the courts seem to have taken a step further, holding that the finding and treatment of antitrust conducts are outside the purview of arbitration, thereby preempting the possibility of the parties resorting to arbitration to resolve their antitrust disputes.In Changlin v. Shell, in which Changlin accused Shell of abusing its dominant market position, Shell argued that the court lacked jurisdiction due to the presence of an arbitration clause. The court ruled that as antitrust cases involve public interest and therefore, an arbitration clause cannot exclude the court’s jurisdiction. Ultimately, the SPC affirmed the court’s authority to hear the case notwithstanding the arbitration clause. Nevertheless, it remains to be seen how subsequent judicial practice will develop, especially with respect to whether and how other aspects of the parties’ disputes (such as contractual damages related to antitrust claims) can be arbitrated, and whether and how a foreign arbitral award (to the extent it involves antitrust elements) will be enforced in China. [Article 3]

3. Court will not accept standalone actions for affirming monopolistic conducts

The New Antitrust JIs provides that “Where a plaintiff, under the Anti-monopoly Law, directly brings a civil lawsuit to a people’s court, or brings a civil lawsuit to a people’s court after the issuance of a decision by an anti-monopoly law enforcement agency in respect of the suspected monopolistic conduct, and such lawsuit otherwise meets the conditions for case docketing prescribed by law, the people’s court shall docket the case...”. As indicated by the SPC ruling in the monopoly dispute case Wang v. Liang[3], if a plaintiff’s filing of the lawsuit does not directly address rights and obligations, and the plaintiff does not intend to rely on the affirmation judgment to dispositively resolve the civil dispute between the parties, the lawsuit for affirmation of monopolistic conduct will be considered devoid of litigation merits and the case shall be dismissed. [Article 2]

4. Calculation of time limit for actions

Consistent with the PRC Civil Code, the time limit for action for claiming damages for monopolistic conduct is three years, commencing from the date on which the plaintiff becomes or should have become aware that its rights and interests were harmed by such conduct.

If the plaintiff files a complaint to an antitrust enforcement agency, the time limit for action will be interrupted or recalculated, depending on the circumstances of the antitrust investigation: (a) if the agency decides not to accept the case, to withdraw the case, or to terminate the investigation, the time limit for action will be re-calculated from the date on which the plaintiff becomes or should have become aware of such a decision; (b) if the agency finds that the conduct in question constitutes monopolistic conduct, the time limit for action will be interrupted and will be recalculated from the date on which the plaintiff becomes or should have become aware that the relevant administrative decision with a finding of monopolistic conduct has taken effect. [Article 49]

5. PRC courts’ extra-territorial jurisdiction over foreign monopolistic conducts

Following the approach set forth in Article 2 of the AML[4], the New Antitrust JIs clarifies that the PRC courts shall have jurisdiction over cases where any foreign monopolistic conduct has the effect of eliminating or restricting competition in China’s market. In 2023, Guangzhou Mengbian Information Technology Co., Ltd. (“Mengbian”), an e-commerce company on the Amazon platform, filed a lawsuit in China alleging that Amazon abused its dominant market position by refusing to deal with Mengbian. Although this alleged conduct occurred outside of China, the Guangzhou Intellectual Property Court docketed the case based on Article 2 of AML. [Article 6]

II. Market Definition

6. Lightened the plaintiffs’ burden of proof for market definition

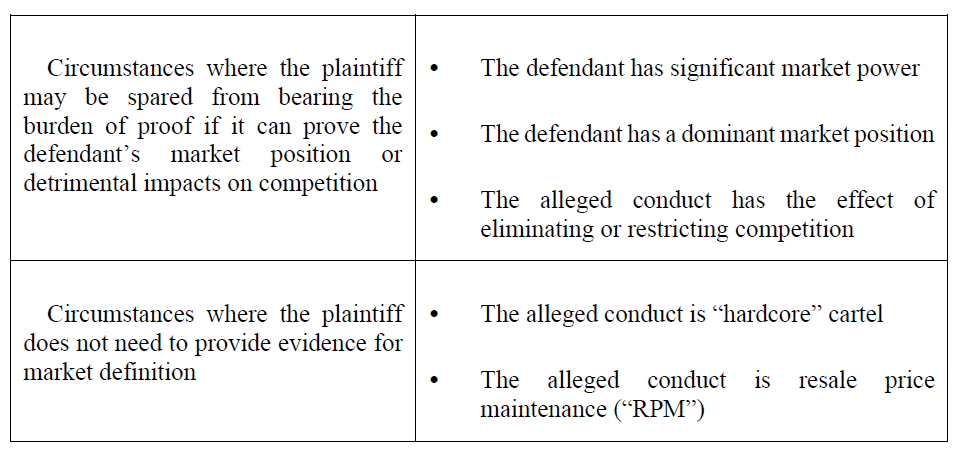

The New Antitrust JIs clarifies that the plaintiff shall bear a graded burden of proof in respect of its definition of the relevant market in connection with alleged monopolistic practices.

In principle, the plaintiff shall be responsible for defining the relevant market in which the defendant operates, and providing sufficient evidence or rationale for such definition. However, if the defendant has significant market power or the alleged conduct has the apparent effect of eliminating or restricting competition, the plaintiff’s burden of proof will be lightened or even waived:

The New Antitrust JIs appears to break away from the long-standing PRC practice of using the market definition as the starting point for competition analysis, especially for claims against certain abusive conducts. This trend favors the plaintiffs, especially in cases where claims are made against large digital platform companies. Market definition relating to platforms is complex, and in past judicial practice, plaintiffs generally lack the capability to gather evidence and conduct sophisticated analysis to establish the relevant market. The new provision could significantly ease the burden of proof on plaintiffs. In addition, it warrants continued attention as to whether this principle in the New Antitrust JIs will steer the development of enforcement practice, such that the antitrust enforcers will focus more on the analysis of “market power” and “competitive harm” in their law enforcement process, without adhering to the rigid doctrine of clearly defining the relevant market. [Article 14]

7. Special considerations in connection with defining and analyzing platform markets

In addition to clarifying the general approaches for defining a relevant market, the New Antitrust JIs, by reference to the Anti-Monopoly Guidelines on Platform Economy Sectors (“Platform Antitrust Guidelines”), sets out special considerations with respect to market definition and competitive analysis in the digital sector, including: (a) special methods to gauge the hypothetical monopolist test results, such as decreasing quality and increasing costs, so as to facilitate the assessment of non-price competition between undertakings that is mainly manifested in terms of quality, diversity, innovation, etc. (b) provisions that the parties are allowed to define one or more markets relating to the platform in light of specific circumstances, or define the market around the platform as a whole. [Articles 15, 16, and 17]

III. Monopoly Agreements

8. Criteria for identifying anti-competitive reverse payments

The New Antitrust JIs pays special attention to “reverse payment” or “pay-for-delay”, as observed in the pharmaceutical industry, and emphasizes that the burden of proof can be shifted through correct evaluation of the plaintiffs’ prima facie evidence, easing the difficulties for the plaintiffs to fulfill the burden of proof — for example, a court may deem a horizontal monopolistic agreement exists if the plaintiff proves that (a) “the owner of the generic drug gives or promises to give the generic drug applicant obviously unreasonable compensation in money or in other forms of benefits”; or (b) “the generic drug applicant undertakes not to challenge the validity of the patent of the generic drug or delay entry into the relevant market.” On the other hand, the defendant may defend itself by proving the justification for such compensation. Before the promulgation of the New Antitrust JIs, there have been a few judicial cases concerning reverse payment. For example[5], in December 2021, the SPC, in a patent infringement lawsuit, explicitly stated for the first time that courts need to conduct antitrust review of reverse payment agreements to determine whether such agreements could exclude or restrict competition in the relevant market. [Article 20]

9. Defendants’ burden of proof to show that RPM at issue does not have anti-competitive effects

To implement the relevant provisions of the Amended AML, the New Antitrust JIs clarifies that the burden of proof will be on the plaintiffs for establishing the existence of RPM conduct, and the defendants shall bear the burden of proof to show that such conduct does not have the effect of eliminating or restricting competition. [Article 21]

10. New types of monopolistic practices in the digital sector

In line with the Amended AML and the Platform Antitrust Guidelines, the New Antitrust JIs also addresses the horizontal monopolistic practices achieved by means of data, algorithms, technology, platform rules, and so on, such as unifying prices by virtue of platform rules, automatic pricing by technical means, and data collusion. For vertical monopoly agreements, practices such as “pick-one-side”, searching for lottery, traffic restriction, etc., commonly implemented through platform rules or algorithms may also raise the antitrust red flag. [Article 24]

In addition, the Most-Favored-Nation (MFN) treatment adopted by the Platform may face multiple antitrust exposures, such as horizontal monopoly, vertical monopoly, or abuse of market dominance. So far, we are not aware of any judicial or law enforcement cases directly relating to MFN treatment in China. [Article 25]

IV. Abuse of Dominance

11. Significantly lightened burden of proof for market dominance

The New Antitrust JIs stipulates the evidentiary standards applicable to preliminarily determine the market dominance of an undertaking, including: (a) the undertaking maintains prices significantly higher than the competitive level of the market for a relatively long period of time, or despite a significant decline in product quality for a relatively long period of time, it experiences no substantial loss of users and there is an apparent lack of competition, innovation, and new entrants in the relevant market; (b) the undertaking maintains a significantly higher market share over a relatively long period of time in comparison with other undertakings and there is an apparent lack of competition, innovation, and new entrants in the relevant market. Combined with the provision of Article 14 regarding market definition as discussed above, the plaintiffs’ burden of proof in abuse cases will be further reduced. [Article 29]

12. Key factors in assessing IPR abuse

In furtherance of the Provisions on the Prohibition of Abuse of Intellectual Property Rights to Exclude or Restrain Competition, the New Antitrust JIs refines the factors that shall be considered when determining a dominant market position in the IPR sector, including: (a) the IP itself and the competitive relationship facing downstream products using such IP; (b) the counterparty’s capability; (c) the market innovation trend, etc.

In addition, the New Antitrust JIs clarifies that the mere ownership of IP cannot be presumed to establish a dominant market position. [Article 33] For more detail, please refer to our article Highlights on China’s New IPR Antitrust Rules and Draft SEP Antitrust Guidelines[6].

13. Refined factors for identifying abusive behaviors

In furtherance of the Provisions on the Prohibition of the Abuse of Dominant Positions, the New Antitrust JIs sets out behaviors that are considered abusive, including unfair pricing, selling products at a price below cost, refusal to do business with transaction counterparties, restricting its transaction counterparties to only trade with the undertaking or with an undertaking designated by the undertaking, tying products and discriminating among transaction counterparties. Below we set out the main stipulations:

To determine unfair pricing, the courts may take into account additional factors such as the yield, the duration of an unfair price, whether the pricing is sufficient to eliminate or restrict competitors with equal efficiency in the relevant market, etc. [Article 36]

To find out whether an undertaking abusively refuses counterparties, courts shall consider whether the refusal obviously eliminates or restricts the effective competition in the upstream market or downstream market. Meanwhile, the New Antitrust JIs pays special attention to the seemingly innocuous refusals, such as the refusal to make ones’ products compatible with certain goods, platforms, or software systems, or the refusal to allow access to technologies, data, or platform interfaces in certain platform. [Article 38]

To ascertain whether restrictions on transactions, tie-in sales, and discriminatory treatment are abusive in nature, the New Antitrust JIs lays out specific forms of conduct and possible justifications therefor, particularly in the field of the digital economy, by factoring in IP rights, security, business models, protection of consumers’ rights and interests, etc. The following are some examples for justifiable acts: (a) restriction on transaction may be necessary to prevent improper behaviors having negative impact on the platform; (b) tie-in sales may be necessary to maintain the normal operation of the platform; and (c) differential treatments could be random transactions based on fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory platform rules. [Articles 39, 40, and 41]

V. Civil Liability

14. Clarified scope of damages

The New Antitrust JIs delineates the scope of damages claimable, including direct losses and anticipated loss of profit, and specifies the methods for calculating damages, such as methods based on prior comparison, comparable market, comparable operators, etc. On the other hand, the New Antitrust JIs provides that courts may elect to take it into their own hands to determine a reasonable amount of damages, if this practice may help mitigate the obstacles for the plaintiffs to obtain appropriate damages. [Article 44]

In addition, the New Antitrust JIs specifies the types of reasonable expenses that a plaintiff may claim, including reasonable market research fees and economic analysis fees, as damages, thus supporting the plaintiffs in carrying out relevant market definition and other professional analysis, and reducing the litigation costs of them. It is worth noting that JD.com was awarded the amount in dispute against Alibaba of CNY 1 billion in the first instance trial.[7] Now the case is in the second instance phase and the court’s calculation method for damages will be closely monitored. [Article 45]

15. Consolidated damages arising from multiple monopolistic practices

Under the New Antitrust JIs, where a number of alleged monopolistic conducts are interrelated and cause indivisible overall losses to a plaintiff in the same or several relevant markets, courts should consider the losses in its entirety when determining damages. [Article 46]

16. PRC courts may order defendants to take measures to restore competition

Under the New Antitrust JIs, where the conduct concerned constitutes a monopolistic practice, a plaintiff may seek injunctive relief, damages, and may ask the court to order the defendant to “bear the legal liability for taking necessary actions to restore competition”. This provision expands the scope of the courts’ authority on remedies, which previously was reserved to law enforcement agencies. It remains to be seen how this power will be exercised. A notable example would be, in the sanction against Tencent by SAMR on 24 July 2021, in order to restore competition, Tencent was required to take actions including not reaching, or effectively reaching, exclusive copyright agreements with upstream copyright holders.[8][Article 43]

[Note]

[1] Please see [2020] Zui Gao Fa Zhi Min Zhong No. 1137.

[2] Please see [2022] Zui Gao Fa Zhi Min Zhong No. 1276, Longsheng v. Yushidu and Honeywell; [2019] Zui Gao Fa Zhi Min Xia Zhong No. 46, Shell v. Huili.

[3] Please see [2021] Zui Gao Fa Zhi Min Zhong No. 2131, Wang v. Liang.

[4] Article 2 of AML provides that the law shall apply to monopolistic practices in economic activities within the territory of the People’s Republic of China and also apply to monopolistic practices outside the territory of the People’s Republic of China if they eliminate or restrict market competition in China

[5] Please see [2021] Zui Gao Fa Zhi Min Zhong No.388 AstraZeneca Limited v. Jiangsu Aosaikang Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd https://ipc.court.gov.cn/zh-cn/news/view-1881.html.

[6] Please see https://en.zhonglun.com/research/articles/52471.html.

[7] Please see [2017] Jing Min Chu No.156.

[8] Guo Shi Jian Chu [2021] No.67 Decision on Administrative Penalty.