China Ups the Ante on Merger Control: New Guide and Rising Risks

China Ups the Ante on Merger Control: New Guide and Rising Risks

The first half of 2025 saw China’s continuous efforts in developing its merger control regime. Among other things, the State Administration for Market Regulation (“SAMR”), China’s antitrust authority, has bolstered its toolkit by releasing a set of guides on the merger review, as well as penalty against failure to notify cases. On the enforcement front, SAMR has intensified its scrutiny of mergers in sectors such as semiconductors, healthcare, and shipping, extending oversight even to deals falling below the filing thresholds. Against such backdrop, we have identified the following trends that will have implications for businesses in their global or cross-border M&A transactions:

1. New indicators for evaluating competition harm

• SAMR releases China’s first merger review guide using market share and HHI thresholds, aligning with US/EU frameworks.

• Horizontal transactions with >35% market share or post-transaction HHI >1000 and ΔHHI >100 may trigger heightened scrutiny.

• Draft guide on non-horizontal mergers goes even further, suggesting heightened vigilance.

2. Markets with limited relevance to the transaction itself potentially subject to scrutiny

• New rules require parties to identify all markets with any horizontal, vertical, or conglomerate link.

• SAMR may ask for information on markets where a party merely holds 10% share and derives 5% of its revenue.

3. Below-threshold deals may be called in

• SAMR has stepped up enforcement against un-notified deals, as indicated by the first prohibition of a below-threshold transaction.

• At least six below-threshold cases have been reviewed or called in since 2023, mainly in tech and healthcare.

• Even closed deals may be subject to remedies – full rollback was ordered in one case.

4. Competition concern involving ecosystem may take spotlight

• Draft guide calls for new “ecosystem”-based analysis in reviewing mergers.

• No enforcement action has yet been taken based solely on ecosystem theories – but that could change.

5. Landmark case spanning litigation and investigation: Tobishi v. SAMR

• The Beijing IP Court affirms that unconditional approvals foreclose subsequent judicial challenge – stakeholders must raise antitrust objections during the review process, not after clearance.

6. Government subsidy may require disclosure

• SAMR now has express power to request details of government subsidies – domestic or foreign – when reviewing mergers.

• China’s approach differs from the EU’s FSR by embedding review within the merger regime.

1.New Indicators for Evaluating Competition Harm

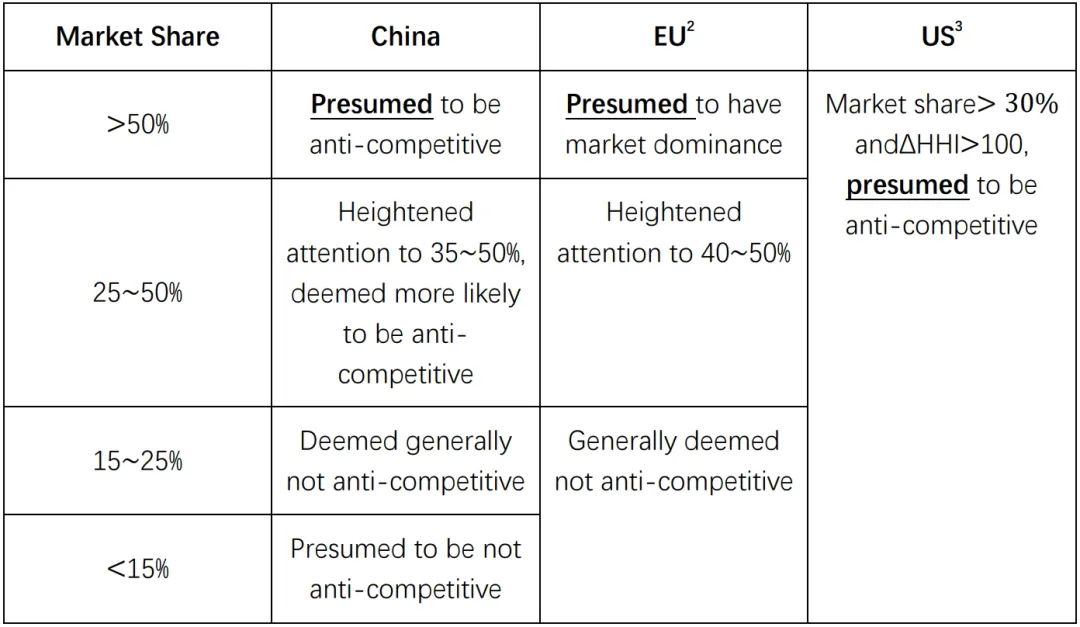

The Guide for the Review of Horizontal Concentrations of Undertakings (“Horizontal Guide”)[1] marks China’s first antitrust guidance for substantive merger review of horizontal transactions. Notably, SAMR introduces quantitative indicators to evaluate competition harm, which, as we observe, converges with the approach in other major jurisdictions such as the US and the EU.

Table 1: Market Share and Competition Concerns (Horizontal Transactions)

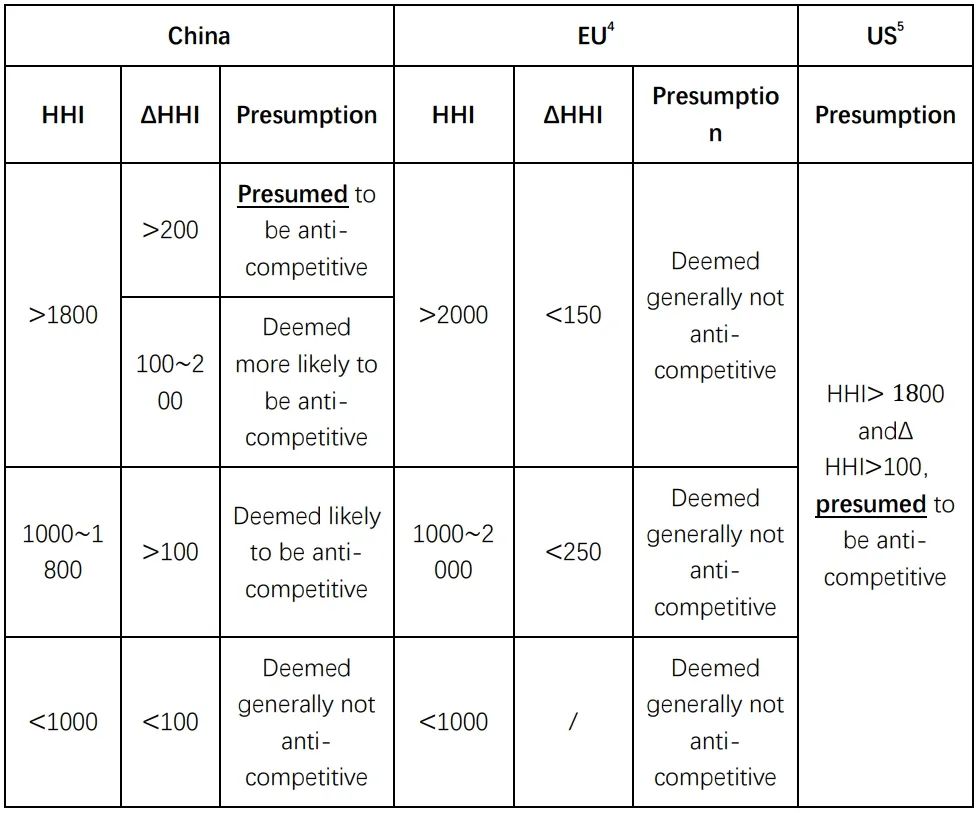

Table 2: HHI and Competition Concerns (Horizontal Transactions)

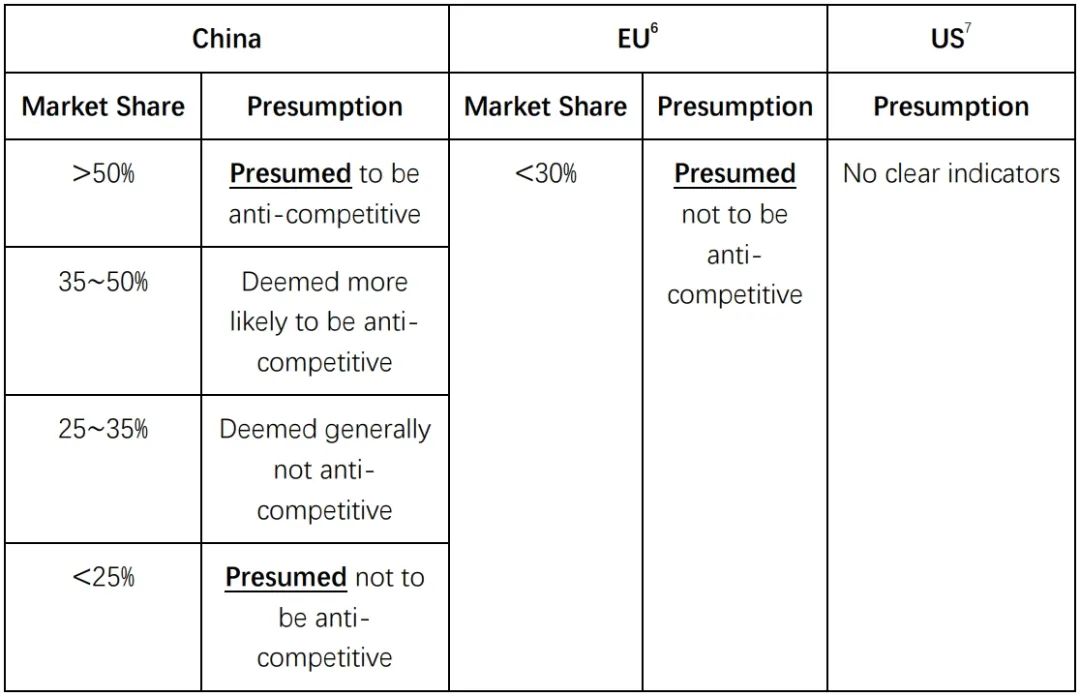

In the latest Guide for the Review of Non-horizontal Concentrations of Undertakings (Draft for Public Comments) (“Non-horizontal Guide”) issued on June 27, 2025, SAMR proposed to introduce a similar set of indicators for evaluating non-horizontal transactions, which in our view are more granular than those adopted by their counterparts in the US and the EU. More details are in the following table:

Table 3: Market Share and Competition Concerns (Non-Horizontal Transactions)

Importantly, SAMR emphasizes that the above indicators are merely starting points to facilitate merger review, rather than conclusive factors. Transaction parties may rebut such presumptions by presenting evidence to the contrary (e.g., see the Horizontal Guide, Chapters V to XI, for more details).

While some may find such indicators somewhat rigid, the two antitrust guides are believed to reflect SAMR’s latest efforts in streamlining China’s merger control review as well as offering a clearer roadmap for compliance. Our analysis based on the 30 conditional clearance decisions published by SAMR to date reveals that the vast majority – 22 cases (73%), involving horizontal transactions – feature deals where the parties’ combined market share fell within 2550%, with post-merger HHI exceeding 1,000 and ΔHHI above 100, suggesting that the indicators closely align with SAMR’s current practice.

2.Markets with Limited Relevance Potentially Included under Scrutiny

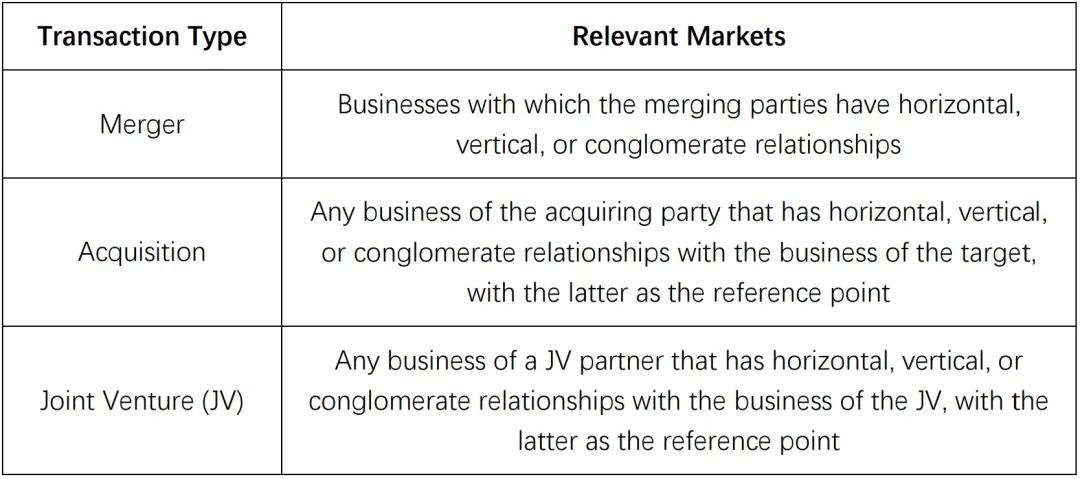

Article 15 of the Horizontal Guide mandates that the parties shall identify all relevant markets that could be potentially affected by the transaction, with the roadmap for defining relevant markets varying based on transaction types, as shown in the following table:

Table 4: Market Definition Roadmap under the Horizontal Guide

Article 16 of the Non-Horizontal Guide attempts to expand such scopes by stipulating that where initial market definition (by way of identifying said relationships) is not sufficient to assess the effect on competition in a market, the parties shall be required define additional markets where (i) the relevant party’s revenue ratio exceeds 5%; and (ii) the relevant market share exceeds 10%.

Our recent experience suggests that the above more expansive approach has already been adopted by SAMR in practice. For example, where a transaction involves complex product portfolios (e.g., chemicals, digital platforms, home appliances, and pharmaceuticals), even if the transaction parties’ businesses have limited connections with the transaction itself, authorities are inclined to require for defining most of the relevant products concerning the target/JV business, significantly expanding the number of relevant markets to be analyzed compared to previous practice.

This may increase the filing burdens for companies having large product portfolios and/or leading market position to qualify a simplified procedure, or even if qualified, to pursue a swift case acceptance and clearance. Whether and how the above approach will be implemented post-Non-Horizontal Guide remains to be seen.

3.Below-threshold Deals May Be Called In

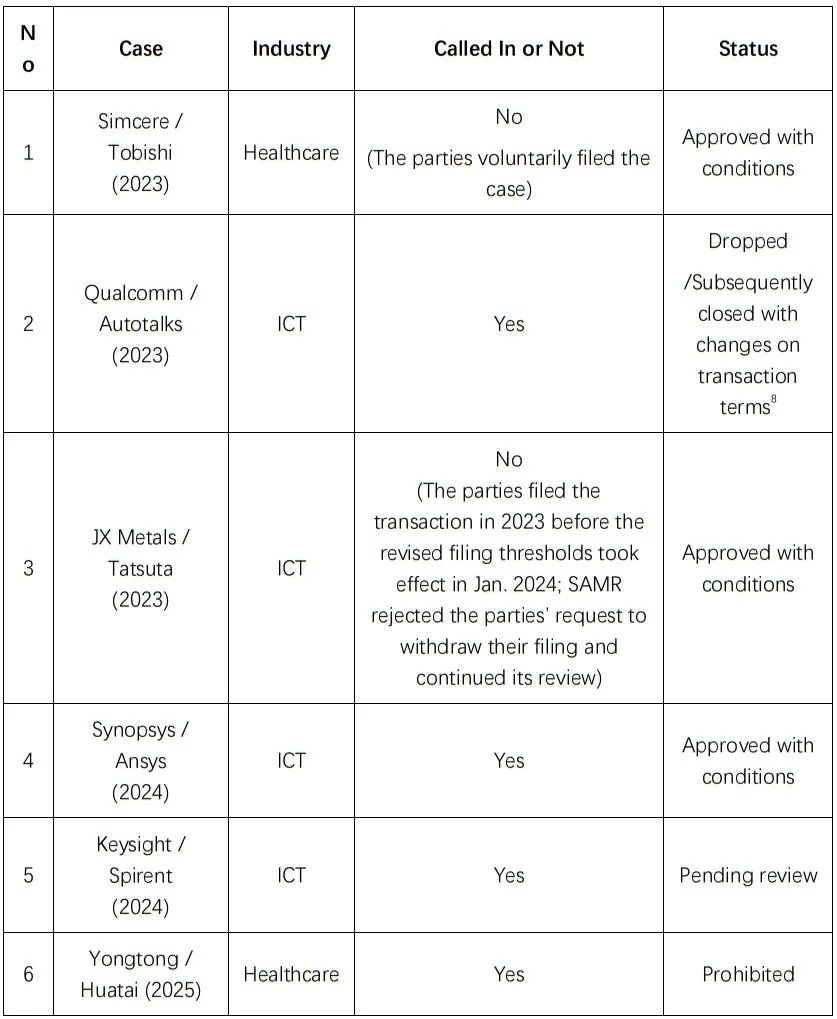

SAMR is empowered by the Anti-monopoly Law (“AML”) to review (upon voluntary filing) or “call in” a below-threshold transaction where there is evidence that such transaction has or is likely to have the effect of eliminating or restricting competition. So far, SAMR has been actively utilizing such power in a number of below-threshold transactions. Some examples are presented in the table below:

Table 5: Summary of Below-Threshold Transactions Reviewed in China

The last case marks the first of its kind where SAMR decides to block a below-threshold merger. In the case, SAMR required full restoration to pre-transaction status – including equity divestiture and dismantling of contractual relationship. It shows Chinese authority’s resolve to adopt all necessary remedies in cases where a transaction has been found to have material competition harms, even though the transaction has been closed for years.

In contrast, the European Commission’s (“EC”) jurisdiction over below-threshold transactions under Article 22 (the referral mechanism from member states) of the EU Merger Regulation[2] was found to be substantially narrowed after the Illumina/Grail case;[3] while US agencies have rarely intervened to investigate transactions below filing thresholds.[4]

In the past few years, SAMR has been increasingly exercising its power in reviewing below-threshold cases, especially in the high-tech and other sectors concerning people’s livelihood. In light of such trend, we recommend that multinationals proactively assess the regulatory requirements in China.

4.Competition Concern Involving Ecosystem May Take Spotlight

Article 70 of the Non-Horizontal Guide explored the evolutions of competition analysis related to “ecosystems” – typically conglomerate transactions that foster the growth and expansion of an ecosystem, broaden product portfolios, generate network effects, and strengthen user stickiness. The antitrust authority may, on the case-by-case basis and based on sound evidence, assess whether an ecosystem operator has the ability and incentive to exclude or restrict competition in the relevant market. The draft guide, however, provides no detailed theory of harm. To date, we are not aware of any platform-related transaction that has been blocked or conditionally approved solely due to non-horizontal concerns. The impact of the final Non-Horizontal Guide will have on antitrust enforcement and its implications for ecosystem (e.g., a digital platform) operators in their transaction remains to be seen.

For reference, the EC is currently seeking public comments on its merger control guidelines.[5] As part of such consultation, the EC proposed several potential theories of harm it has detected in the digitalization of the economy, such as leverage of market power into a new market, targeted foreclosure, and strengthening the ecosystem.

5.Landmark Case Spanning Litigation and Investigation: Tobishi v. SAMR

The recent Tobishi v. SAMR case[6], adjudicated by the Beijing Intellectual Property Court (“Beijing IP Court”), marks China’s first administrative lawsuit challenging merger review decision – the Simcere/Tobishi case. The following are noteworthy takeaways:

(1) An unconditional cleared case generally cannot be challenged in court

The Beijing IP Court ruling affirms a three-step redress process for merger review cases: a) administrative decision, b) administrative review, and c) litigation, ensuring procedural safeguards for the involved parties. However, it also stipulates that an unconditional clearance decision shall not be challenged as a general rule, as such clearance does not alter or obstruct the parties’ rights or obligations. This may have procedural implications, as it essentially narrows the parties’ options to contest a transaction post-clearance, especially in a hostile takeover context. Consequently, the window for antitrust challenge will be substantially curtailed, primarily confined to the review stage or earlier.

(2) Prioritizing “non-prohibition” enforcement

In the Simcere/Tobishi case,[7] instead of outright prohibiting the transaction, SAMR opted to approve it with remedies designed to address horizontal and vertical concerns arising therefrom (including terminating the exclusive agreement with the upstream supplier, divesting the R&D business, etc.). The court’s judgement supported SAMR’s position and made it clear that prohibition is not the default remedy in a merger review. Instead, SAMR’s primary objective is to mitigate competition concerns, rather than to block transactions. With this understanding, going ahead, companies could have more confidence and an expanded set of approaches in negotiating with SAMR the commitments to address potential competition concerns. Our statistics show that, in H1 2025 alone, SAMR cleared 310 transactions unconditionally, approved only four with remedies[8], and blocked none[9], highlighting the authority’s inclination towards granting (conditional) clearance rather than resorting to prohibition.

(3) SAMR’s competition assessment methodology

The Beijing IP Court judgment also reveals SAMR’s evidence-gathering practices during the merger review, including: (i) consultations with industry authorities, associations, customers, and relevant stakeholders; (ii) independent economic analysis; and (iii) expert panels. Understanding these measures can help merger parties better anticipate and address the regulatory process.

6.Government Subsidy May Require Disclosure

For the first time, China’s Horizontal Guide incorporates government subsidies into their antitrust regulatory framework. Article 82 provides that where there is evidence proving that subsidies (domestic or foreign) received by the parties may harm market competition, the authorities may require detailed subsidy disclosure, and assess its adverse market impacts.

This reflects China’s heightened attention to subsidy-driven distortions in market competition. The EU established a standalone Foreign Subsidies Regulation in 2023 to review and investigate foreign subsidies; the US also requests for disclosure of foreign subsidies from certain countries, including China, in HSR filing.[10] In contrast, China chose to embed subsidy review within its existing merger control regime. Notably, China’s approach targets all government interventions – whether foreign or domestic. We will continue to monitor how such mechanisms apply in practice.

[Note]

[1]See:https://www.samr.gov.cn/zw/zfxxgk/fdzdgknr/fldzfes/art/2024/art_635d601b816e412e88265f83d4f6794d.html.

[2]The EC has no direct power to review below-threshold transactions. Its jurisdiction was once expanded under the Article 22 of the EU Merger Regulation to allow member states to refer such transactions to the EC. However, in the Illumina/Grai case, the European Court of Justice made it clear that the EC would not have jurisdiction to review below-threshold transactions, if the member states referring the transactions have no jurisdiction over such transactions under their own national rules.

Notably, several member states, including Italy, Hungary, and Denmark, have the power to review transactions that do not meet the thresholds based on their national laws and regulations. Therefore, according to the ruling in the Illumina/Grail case, it is still possible for the EC to review cases referred from these member states.

[3]See:https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:62022CJ0611.

[4]Though neither the FTC nor the DOJ has the authority to require notification of transactions that do not meet the notification thresholds, both agencies have the authority to investigate any transaction that raises competitive concerns.

[5]See:https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_25_1141.

[6]See:https://www.samr.gov.cn/fldes/sjdt/gzdt/art/2025/art_1c787b924f804e36977dd1850c41a551.html;

https://www.samr.gov.cn/fldes/sjdt/gzdt/art/2025/art_1c787b924f804e36977dd1850c41a551.html.

[7]See:https://www.samr.gov.cn/fldes/tzgg/ftj/art/2023/art_90a71deadd224689b026920807c0389c.html.

[8]See:https://www.samr.gov.cn/fldes/tzgg/ftj/art/2025/art_0c6700f56f174bee8fd90dc8ecb6ffcc.html;

https://www.samr.gov.cn/fldes/tzgg/ftj/art/2025/art_d7752467113c49d1b41168db859e1a67.html;

https://www.samr.gov.cn/fldes/tzgg/ftj/art/2025/art_3071f2aa67c94a3882fec719f45bd8c3.html;

https://www.samr.gov.cn/fldes/tzgg/ftj/art/2025/art_3a7b235d312840b5b19c538a6773af5f.html.

[9]As introduced above, SAMR recently blocked one closed below-threshold transaction.

[10]See:https://competition-policy.ec.europa.eu/foreign-subsidies-regulation_en;

https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/HSR-Form-Updates-FINAL-POSTED-01-02-25.pdf.